Attorneys’ Fee Awards in Delaware: Some Much-Needed Data to Calm the Waters

Fees awarded to plaintiffs’ lawyers in Delaware derivative suits and class actions have recently become the subject of public controversy and policy debate. The $345 million fee award in Tornetta v. Musk has attracted the most attention and, together with a small number of other high-profile cases, has triggered the current debate. A draft paper by Joseph Grundfest and Gal Dor, which collected twenty cases of high fee awards over the past sixteen years, added fuel to the fire. A raft of press reports followed, with titles such as “Report Finds Delaware Court Jumbo Fees Rival Federal System.” Grundfest and Dor, and the press reports in their wake, focus on a small subset of cases in which fee awards were seven or more times the plaintiffs’ attorneys’ lodestar—that is, the hours lawyers devoted to a case multiplied by their hourly rate.

In a new paper, “Attorneys’ Fee Awards in Delaware: A Normative and Empirical Analysis,” we analyze ten years of comprehensive data to investigate whether such high fees are common or reflect a systematic problem with Delaware’s fee-award regime. Based on the data, we conclude that the awards the Court’s critics have highlighted are extreme outliers: among settled and tried cases, they account for about 1% of all fee awards. They are a byproduct of Delaware’s approach to fee awards, which is designed to give plaintiffs’ lawyers incentives to achieve the best possible outcomes for their clients (i.e., shareholders in a class action and the corporation in a derivative suit). We further find, contrary to the Court’s critics, that fees in Delaware cases are similar to those in federal securities class actions.

Delaware Supreme Court case law has long established that the Court of Chancery should award fees to plaintiffs’ lawyers based primarily on a percentage of the recovery or other benefit that the litigation confers on the corporation or the shareholder class. The percentage awarded increases for settlements that occur later in the litigation process and for cases that go to trial. The Supreme Court has further held that the Court of Chancery has discretion to adjust fees based on other factors, including the time plaintiffs’ attorneys devote to a case. This approach is consistent with economic analyses of incentive alignment between plaintiffs’ attorneys working on a contingency-fee basis and their clients.

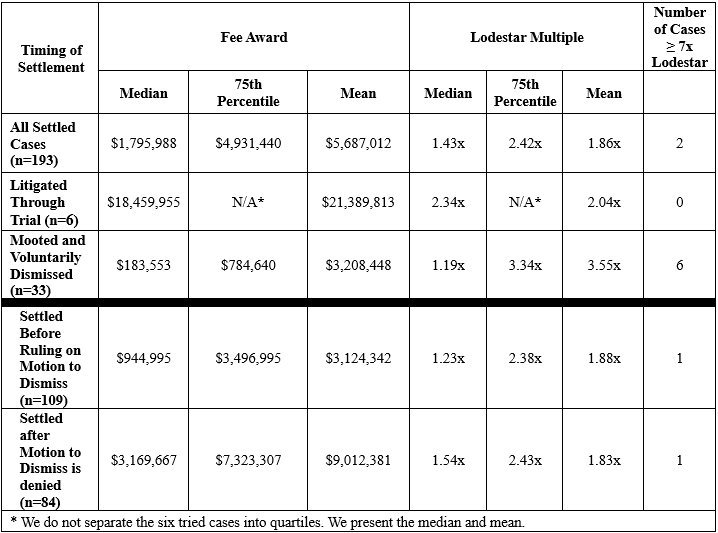

Our central findings are summarized in Table 1 below. This table presents cases classified based on the stage of a case’s resolution (i.e., settled, tried, or voluntarily dismissed as moot), irrespective of whether they resulted in a monetary recovery or a non-monetary recovery (e.g., governance changes, deal amendments, etc.).

Table 1

Fee Award and Lodestar Multiple by Timing of Resolution (n=232)

In settled cases, mean and median fees are 1.86 and 1.43 times the attorneys’ lodestar, respectively. Even at the 75th percentile, fees are 2.42 times the lodestar—far short of the 7x fees that have drawn critical attention. The lodestar multiples in the relatively small number of cases that went to trial are somewhat higher, but not dramatically so. Fees in those cases, and in cases that settled after a ruling on a motion to dismiss, are consistent with the Supreme Court’s guidance—and with economic analyses of incentive-compatible fee structures—according to which the percentage of the benefit awarded should be higher for cases that progress further into the litigation process. Among settled cases, only two of 193 resulted in fees seven times the lodestar. This pattern is similar to that observed in federal securities class actions.

Table 1 also includes cases that became moot once defendants met the plaintiffs’ demands and the plaintiffs voluntarily dismissed their case. In general, plaintiffs’ counsel and defendants negotiate fees in these mooted cases without the Court of Chancery’s involvement. As a result, there is typically no record of the lodestar. The mootness fees reported in Table 1 are those paid in cases for which lodestar data were available in the docket because the parties were unable to agree on a fee, and therefore triggered the Court’s review. As reflected by the median mootness fee, absolute fee levels in these cases are relatively low. Yet, because mootness tends to occur earlier than the other outcomes in the sample, the hours recorded are often lower, which can produce mean lodestar multiples higher than in settled or tried cases.

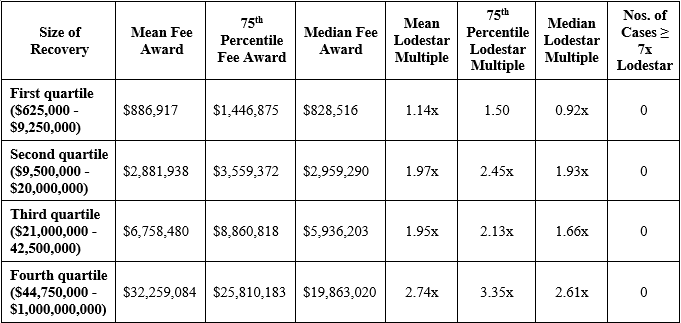

The Tornetta case and other high lodestar-multiple cases on which the Court’s critics focus are cases with very high shareholder recoveries. This is not surprising. Because fees are based primarily on a percentage of the plaintiffs’ monetary recovery or other benefit provided, one would expect some high-recovery cases to result in fees that are a high multiple of the lawyers’ lodestar. The hours a plaintiffs’ lawyer devotes to a case are not necessarily proportionate to the value of the potential recovery. Table 2 presents lodestar multiples by size of the recovery in cases with only monetary recoveries. We exclude cases with non-monetary remedies here because the value of such remedies is difficult to quantify and, therefore, subject to disagreement among the parties. As one would expect, mean, median, and 75th percentile lodestar multiples rise with the size of the plaintiffs’ recovery. The results, however, remain far below the levels that dominate the critical public discussion.

Table 2

Fee Award and Lodestar Multiple by Size of Recovery (n=87)

The bottom line is that the high fee awards on which the critics concentrate constitute a thin tail of the distribution of settled and tried cases. Among settled cases in Table 1, only two out of 193 provided 7x awards to plaintiffs’ counsel. (Those cases do not appear in Table 2 because the remedies were not solely monetary.) A small number of additional high-multiple awards arose in cases that plaintiffs voluntarily dismissed as moot. Among these, there is the case challenging Facebook’s effort to restructure its equity to allow Mark Zuckerberg to maintain control with a minority shareholding. Facebook abandoned that plan on the eve of trial, and the plaintiffs dropped their case. The plaintiffs’ lawyers received fees of $68.7 million, which amounted to a lodestar multiple of 8.15. Other cases were more typical of mootness cases, with fees ranging from under $1 million to about $2 million, but with high lodestar multiples because they were dropped with relatively little litigation effort.

The visibility of outliers makes them politically salient, and indeed a few outliers are what triggered the current discussion in Delaware about a possible legislative response. From a policy perspective, however, we question whether the statistical tail should wag the dog. Occasional high fees in high-recovery cases are a natural result of a regime that provides plaintiffs’ lawyers with an incentive to pursue the largest recovery they can obtain for shareholders—in high and low recovery cases alike.

Potential responses would include reducing percentage fees in high-recovery cases or capping fees—for example, at four times lodestar—as Texas does in class actions. These measures would address the 1% outliers at the expense of impairing incentives in other cases.

A lower percentage fee, even just for high recovery cases, would tend to reduce plaintiffs’ attorneys’ incentives to obtain the best recovery for their clients. In some cases, the expected fee may still be high enough to keep the attorneys’ incentives aligned. But in cases requiring the greatest amount of legal work, the incentive to press forward for the best recovery for shareholders could be impaired.

A lodestar-based cap on percentage-of-the-recovery fees would be worse, both from an incentive and judicial economy perspectives. Plaintiffs’ lawyers facing a lodestar-based cap would have no incentive to settle cases early for high amounts. Instead, they would have incentives to keep billing hours, in effect at a 4x rate. Then, toward the end of a case, rather than risking a loss, a plaintiffs’ attorney would have an incentive to accept a lower settlement so long as it yields a fee at the cap. This is not to say that plaintiffs’ lawyers would purposely act contrary to the interests of their clients as trial approaches. But they may have little choice. Defense counsel may act strategically by offering them a choice: a settlement that gets them a fee at the cap, or no settlement at all. Creating such a misalignment of lawyer and client interests is a high price to pay for reducing fees in 1% of cases.

Legislative intervention to address outliers is also unnecessary. The Court of Chancery is well-positioned to review fee requests and make adjustments in light of the Supreme Court’s guidance, and it regularly exercises that authority.

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.